St. George Roadcut Reveals Colorful Geology

Sometimes, however, this process is sped up when certain manmade events happen. One of these events is called a roadcut. In many ways, roadcuts are a geologist’s best friend. They provide an opportunity to see what’s below the earth’s surface and get a good look at the unaltered, hidden layers that wouldn’t normally have been seen without these necessities of civilization.

One intriguing roadcut that was just made in 2023 is in the town of Toquerville, about 20 miles northeast of St. George, Utah. This roadcut reveals some rather colorful sedimentary layers, including their curious angle or tilt. This tilt shows us something we can’t easily see elsewhere – what happened beneath the Earth’s surface at a specific point in time and how the nearby Hurricane Fault caused this odd tilt.

The Roadcut

This road cut was made while building what’s known as the Toquerville bypass. It re-routes Highway 17 that runs between La Verkin and Interstate 15. The goal of the bypass is to route traffic away from the small, picturesque town of Toquerville, and have it go to the west, where there is wide open, undeveloped land.

Certainly, construction workers and area residents didn’t expect what to see once the digging was completed. What can now be seen are thin layers of colorful yellow, orange and purplish colors, all tilting in an odd direction. Unfortunately, these layers are not very easy to see, and one can hope that after the construction is complete, people that pass by on the new bypass road will be able to see it.

The cross section of the roadcut reveals four episodes (or layers) of erosional deposition. The first, on top, is the newest addition, consisting of alluvial deposits and area sand that, in recent times, accumulated at the top. Next down is this layer of dense basalt, which was created from a lava flow originating about ten miles north of the site. The third layer down are more alluvial deposits with larger boulders.

The fourth layer is the most interesting. It’s what geologists call the Iron Springs Formation, and it consists of those colorful layers. Plus, it’s the only layer that is at a 20° angle – the other three layers lie flat. The site is quite unusual and, for someone that enjoys geology, it makes for a great geologic mystery to solve.

The Roadcut’s Geology

As mentioned, roadcuts are a geologist’s best friend. And that couldn’t be truer than at the site of the Toquerville bypass. Motorists that will soon be speeding by will only notice the unusually colored stripes on both sides of the road. Most likely, most will not stop and study the roadcut to ponder what’s going on. When the road is complete, hopefully the decision isn’t made to shore up the sides of the roadcut that would hide what was exposed during its construction.

While the roadcut is exposed for all to see, our interpretation comes with a disclaimer: we are not trained geologists. Nonetheless, we offer our observations, viewing this roadcut as a single piece in the intricate puzzle of Southwest Utah’s landscape. Read on, and we’ll explain three aspects to that single puzzle piece.

More…

Support Us

Help us fill up our tank with gas for our next trip by donating $5 and we’ll bring you back more quality virtual tours of our trips!

Your credit card payment is safe and easy using PayPal. Click the [Donate] button to get started:

Pictures

Below are some pictures of what you will see along the way.

The Colors

The multi-colored layers are part of what geologists call the Iron Springs Formation. This chunk of earthen material was deposited during the late Cretaceous period, between 95 to 65 million years ago. To put some perspective to this timeline, you may recall that the dinosaurs went extinct around 65 million years ago. This formation is two major layers above Zion’s famous Navajo Sandstone deposited in the Jurassic period, and two layers below Bryce’s (or Cedar Breaks) colorful Claron Formation.

In the Utah Geological Survey, the Iron Springs Formation is described as: the formation is variously colored grayish orange, pale yellowish orange, dark yellowish orange, white, pale reddish brown, and greenish gray and is locally stained by iron-manganese oxides, which accounts for the reddish colors. When you look at the pictures in this article, do those words describe it? I think they do.

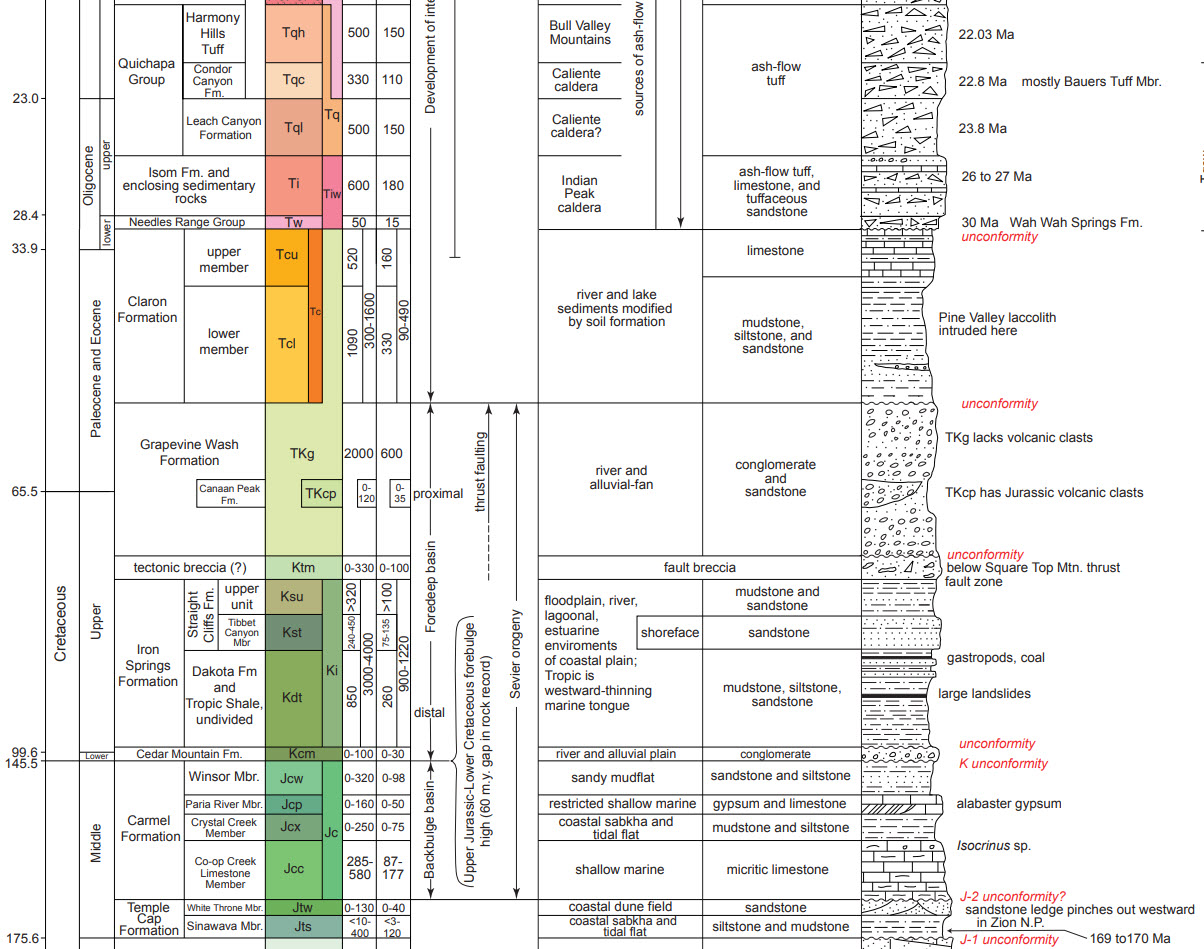

Learn more about the various formations in Southwest Utah by following these steps:

- Go to the Utah Geological Survey website at: https://geology.utah.gov/map-pub/maps/geologic-maps/

- Then, on the map, select the square over the St. George area (the very lower-left corner).

- In the pop-up, select Open PDF. Since the PDF is a large file, it will take a few moments to download.

- The first page is the colorful geologic map. Scroll down to page 2.

- The stratigraphy chart used in the video is on page 2. Scroll down to find the Iron Springs Formation.

- Below is a snippet of the stratigraphy chart showing the formations near the Iron Springs:

Iron Springs Formation

The Iron Springs Formation is named after a locality that is about ten miles northwest of Cedar City, Utah. However, the formation is exposed mainly around the Pine Valley Mountains. In other parts of Utah, this formation is called the Straight Cliffs Formation. The two formations aren’t exactly the same but were deposited about the same period of time and consist mostly of the same Earthen material.

In the Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument, about 90 miles east of the roadcut, sits the massive Kaiparowits Plateau. Most of the plateau is made up of the Straight Cliffs Formation. The Iron Springs Formation near St. George shares many of same characteristics to what’s seen on the Kaiparowits.

Now about the colorful layers. During the Cretaceous period, this large area was swampy and consisted of a lot of organic material. When that organic material was buried by the formations above it, heat and pressure mineralized the organic material. The pressure came from the weight of the additional earthen material above it. Millions of years later, thanks to erosion, the material was exposed to our atmosphere, which in turn oxidized the various minerals and created an array of colors.

This same process, where minerals were oxidized and created colorful scenery, has occurred in other places of the Southwest. One formation in particular is called the Chinle Formation. It’s the remains of another swampy time in Earth’s history. It’s two formations below the Navajo Sandstone Formation mentioned earlier. The Chinle is famous for creating what is now the Painted Desert in Arizona and the Paria townsite in Utah, both having very colorful scenery.

The Angle

How was that curious angle created? It was the fault, of the Hurricane Fault. This major fault is just one mile to the east of the roadcut. As you may know, the Hurricane Fault is the western boundary of the Colorado Plateau and is the fracture where land on the east side uplifted over a mile high creating the plateau.

The uplift is the reason for the uniquely level and layered geology on the east side of the fault. On the west side of the fault, the geology is jumbled up and crumpled. The land closer to the fault also sank.

The same geologic formations on the west side of the fault exist on the east side, but at a different elevation because of the uplift. At the roadcut, the elevation of the Iron Springs Formation is about 3,000 feet (900 m). On the east side of the fault in the Colorado Plateau, it is exposed at 6,000 to 7,000 feet (2,000 m). This is where it is called the Straight Cliffs Formation, mentioned earlier. That offset is about 4,000 feet (1,220 m), meaning the formation uplifted and rose quite a distance.

When the land on the east side of the fault rose, it tilted slightly to the east. The opposite occurred on the west side of the fault. This mainly happened because of the Basin and Range Province, between the Hurricane Fault and the Sierra Nevada Mountains in California, was being stretched apart, causing the land closest to the fault to sink. Watch the video for an animated diagram showing the tilting action.

- See our article on Southwest Utah’s Triple Junction that explains more details about the Hurricane Fault and the Colorado Plateau

This is most likely the reason why we see the tilt in the roadcut. The small hills and ridges near the roadcut are also tilted the same direction – sinking to the east and raising towards the west.

Missing Formations?

In our roadcut, between the colorful layers of the Iron Springs Formation and the next visible layer above containing alluvial deposits, there are a few formations missing. When a layer is missing, it is known as an unconformity. We know the layer is missing because in other areas, the formation exists.

Think of an unconformity as a hamburger with layers such as buns, hamburger patty, tomatoes, pickles and lettuce. The hamburger is cut in half and the patty is removed. Between the two halves, there is now an unconformity on one side, the side with the patty missing.

Great Unconformity

The most well-known unconformity is in the Grand Canyon. It’s known as the Great Unconformity. Here, it is easy to see that several large layers of geology were removed by erosion. It’s a mystery as to how big they were or what material they consisted of. The unconformity in the roadcut isn’t as big but there are a few missing formations nonetheless. Plus, we know what layers are missing and thus what they consisted of.

One well-known formation that is missing is the Claron Formation. The Claron is famous for the hoodoos of Bryce Canyon National Park and other locales in Utah. The Claron is exposed and visible on both sides of the Hurricane Fault. Near the roadcut, it is visible near the base of the Pine Valley Mountains.

Fifty miles north of the roadcut, in a place called Parowan Gap, a large outcrop of Claron Formation can be seen sitting on top Iron Springs Formation. This is what the area around the roadcut may have looked like:

Refer to the stratigraphy chart from the Utah Geological Survey referenced earlier to see where the Iron Springs Formation is in relation to the Claron. The Claron is basically two formations above the Iron Springs. So, between the colorful layers we see in the roadcut and the alluvial deposits above it, there used to be two other significant rock layers.

Summary

Isn’t it amazing to see how all the pieces of a very large jigsaw puzzle come together? It’s why geology is so fascinating to us. Yes, this landscape is beautiful but isn’t it just a little more interesting when you know more about its complex nature? One doesn’t need to be an expert in geology to see the puzzle pieces that put together the scenery of Southwest Utah.

Now that you know more about this roadcut, we hope that when you take road trips from now on, you’ll pay a little more attention to the roadcuts you drive through and wonder what geologic story they are telling. You might also start to wonder what’s just below the surface of the landscapes you’re passing over and what lays just below the surface.

Trip Map

To help plan your trip, use our interactive Google Map below. Be sure to switch to Satellite view to see the terrain.

Learn more about our maps.

Comments

Read and leave comments about this post on YouTube.

Support Us

Help us fill up our tank with gas for our next trip by donating $5 and we’ll bring you back more quality virtual tours of our trips!

Your credit card payment is safe and easy using PayPal. Click the [Donate] button to get started: